Reading view

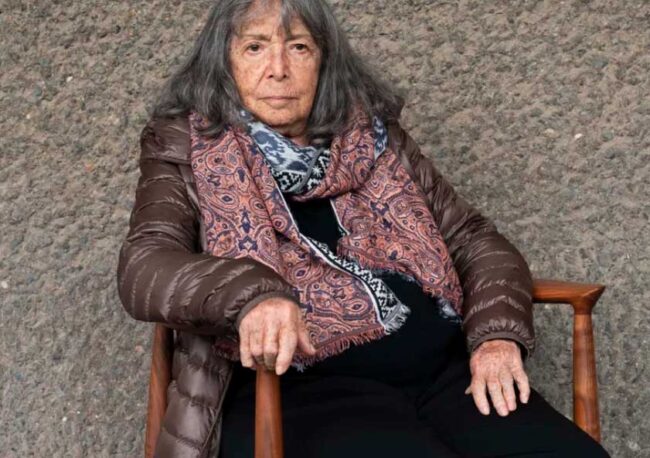

Beatriz González: The Artist of Colombia’s Political Memory (1932-2026)

Beatriz González, one of Latin America’s most influential contemporary artists, whose boldly colored, deliberately unrefined paintings and installations confronted Colombia’s long history of political violence, public mourning and social inequality – while also reshaping the country’s most important public art collection – died on Jan. 9, 2026, at her home in Bogotá. She was 93.

Her death was announced by the Banco de la República, Colombia’s central bank, where for more than four decades she played a decisive role in shaping the institution’s cultural mission and its vast art collections. In a statement, the bank described her as “an essential figure in Colombian art and culture” and “a masterful narrator of memory.”

González was not only a prolific artist but also a historian, curator, educator and critic — a rare figure who helped define how Colombia would see its art, its past and, ultimately, itself. “Artists exist so that memory is not thrown in the trash,” she once said, a line that came to stand as a quiet manifesto for a career devoted to preserving what official histories often erased.

Born in Bucaramanga in 1932, González came of age during La Violencia, the brutal civil conflict that engulfed Colombia between 1948 and 1958. That formative experience would leave an indelible mark on her work. After briefly studying architecture, she enrolled at the University of the Andes in Bogotá, graduating with a degree in fine arts in 1962. She later studied printmaking in Rotterdam and counted among her teachers the influential critic Marta Traba, who helped shape modern art discourse in Latin America.

González’s early work drew attention for its irreverent treatment of European art history and Colombian popular imagery. Her critical view of “good taste” led her to reject academic refinement in favor of what the art critic Germán Rubiano described as an approach that was consciously unpolished and deliberately opposed to sophistication.

She appropriated masterpieces by Manet, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, flattening their compositions and translating them into the visual language of curtains, furniture and household objects. Armoires, beds, trays and even wallpaper became supports for paintings marked by compressed figures and bold color palettes — a strategy that blurred the boundary between high art and domestic life.

One of her earliest and most discussed works, The Sisga Suicides (1965), reimagined a newspaper photograph of a young couple who drowned themselves in a dam outside Bogotá. Rendered in vivid, almost cheerful colors, the painting exposed the uneasy coexistence of tragedy and banality in Colombian public life — a theme that would recur throughout her career.

By the 1980s, González’s art took on an increasingly overt political tone. Press photographs of presidents, massacres and grieving families became central to her work. She painted them repeatedly, transforming news images into objects of repetition and contemplation, as if to ask how a society becomes accustomed to its own suffering. “It’s been a critique of power that has permeated my work,” she told ArtReview in 2016. “For that very reason, I don’t think of it as ‘political’; it has an ethical commitment.”

Her focus on mourning was particularly stark in works depicting mothers weeping after the 1996 Las Delicias massacre, in which dozens of Colombian soldiers were killed by the FARC guerrilla. These images, stripped of sentimentality, confronted viewers with grief as a collective, inescapable condition. The depth with which González addressed both individual and collective mourning stands among her most significant contributions to contemporary art.

That macabre clarity intensified in the 2000s. In Anonymous Auras (2023), one of her final major works, González installed more than 8,000 printed silhouettes of workers carrying corpses across the wall niches of Bogotá’s Central Cemetery. The figures – anonymous, repetitive and almost ritualistic – transformed the cemetery into a monumental archive of loss, honoring victims whose names were never recorded.

“Artists exist so that memory is not thrown in the trash”

Parallel to her artistic production, González exerted extraordinary influence as a curator and cultural policymaker. Beginning in the 1980s, she became a close collaborator of the Banco de la República’s cultural division, serving as a researcher, curator and longtime member of its advisory committee on visual arts. In that role, she helped guide the formation of a national art collection with a distinctly Colombian focus, while insisting on dialogue with international works of the highest quality.

Few individuals knew the Central Bank’s art collection as intimately as González. Over more than forty years, she worked alongside successive generations of curators, historians and collectors, helping to consolidate one of the most important public art collections in Latin America.

In 2020, she donated her personal archive and library — nearly 100,000 documents — to the Banco de la República to ensure free public access. The archive documents not only her artistic practice but also her work as an educator, curator and historian, and provides an unparalleled record of Colombian art, politics and visual culture.

Her institutional impact reached beyond the Central Bank. At the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá (MAMBO), she founded the influential School of Guides, a pioneering program for museum education that trained figures who would later become leading artists and curators. From 1989 to 2004, she served as chief curator of the Museo Nacional de Colombia, where she reorganized the permanent collection and helped redefine the country’s historical narrative through art.

International recognition came steadily. Her work appeared in Documenta 14, the Berlin Biennale and the landmark exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985.” Major retrospectives were held at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the CAPC in Bordeaux. In 2026, the Barbican Centre in London is set to host her first major retrospective in the United Kingdom.

González received numerous honors, including Colombia’s Premio Vida y Obra and honorary doctorates from the University of the Andes and the University of Antioquia. In 2025, the city of Bogotá awarded her the Civil Order of Merit, recognizing her invaluable legacy and profound influence on the nation’s cultural life.

Yet she remained skeptical of accolades. She preferred to speak of discipline, research and responsibility — and of the obligation, as she saw it, to bear witness. From a childhood habit of collecting film-star postcards to a lifetime spent gathering images of state violence, Beatriz González devoted herself to the stubborn preservation of memory and to an unapologetic voice in Colombian contemporary art.

Read the Banco de la República’s tribute (in Spanish) to Beatriz González, written by Claudia Cristancho Camacho of the Cultural Section and Art Collection.

Untitled Art Fair in Miami Spotlights Hard-to-Define Artists

In a $2.2 Billion Week, the Art Market Finds Its Footing

Colombia’s National Museum Marks 200 Years with “Inspire, Move, Convoke”

Two centuries after its founding in the turbulent aftermath of the Wars of Independence, the National Museum of Colombia is marking its bicentenary with one of the most ambitious exhibitions in its history. Inspirar, conmover y convocar: el Museo de la nación (1823–2023) opens this week in Bogotá, inviting visitors to reflect on 200 years of scientific curiosity, cultural formation, and collective memory in a country still redefining its national narrative.

The anniversary is more than a celebration of institutional longevity. It is a moment of self-examination for a museum conceived during the birth of the Republic and shaped by generations of scientists, historians, artists, and citizens. The museum was created by law on July 28, 1823, and inaugurated the following year, rooted in the vision of plenipotentiary Francisco Antonio Zea. During his diplomatic mission in Europe, Zea recruited a cohort of naturalists – including José María Lanz, Mariano de Rivero, Jean-Baptiste Boussingault, and François-Désiré Roulin – to establish a museum of natural history, along with a school of mines, a geography program, and a lithography workshop in the newly constituted Gran Colombia.

These early scientific figures navigated riverways and mountain passes to reach Bogotá, awaiting the young Republic’s final approval of their contracts. Their collections – birds, reptiles, minerals, anatomical studies, botanical illustrations, archaeological finds – formed the foundation of a museum that initially served as a scientific repository for a nation eager to document the vast richness of its territory. Drawings by artists such as Francisco Javier Matís and explorations ordered by Juan María Céspedes gave visual life to the landscapes and ancient cultures the Republic sought to understand and claim as part of its expanding identity.

But as the exhibition demonstrates, the museum’s role has never been static. If the early 19th century emphasized scientific discovery, later decades shifted toward the collection of historical objects, battle flags, ethnographic pieces, and cultural artifacts that broadened the institution’s mandate. Letters exchanged between luminaries De Rivero and Alexander von Humboldt, or between independence-era leaders such as Antonio José de Sucre and Gerónimo Torres, testify to the museum’s early symbolic power. Sucre himself donated the acso– a ceremonial mantle attributed to Atahualpa’s queen – and ordered that defeated Spanish flags be displayed publicly so Colombians could “witness the heroism” of their troops in the war for independence. These gestures turned the museum into a site where political memory and scientific knowledge intertwined.

Two hundred years later, the new exhibition reframes these layered histories through three major sections designed to show how Colombians have constructed, questioned, and reimagined national identity over time.

The first section, Guardar lo que eres (“Preserve What You Are”), looks back at the 19th century through illustrations, botanical specimens, and scientific journalis. These items reveal how the young nation sought to see itself—literally and symbolically—through classification, measurement, and representation. The pieces trace a lineage from early scientific expeditions to the first attempts to map Colombia’s natural and cultural diversity.

The second section, Superar la desventura (“Overcoming Hardship”), addresses conflict and reconstruction. Drawing on flags, legal documents, military archives, and early photographic material, it examines the ways Colombian society has grappled with political rupture, violence, and the challenge of rebuilding. While the exhibition includes objects from independence-era battlefields in Peru, Bolivia, and the Nueva Granada, it also connects more recent struggles with reconciliation, and justice. The curators highlight that conflict-related objects—whether symbols of patriot triumph or testimonies of displacement and suffering—offer crucial insight into how Colombians understand the past and imagine the possibility of peace.

The third and final section is a celebration of life. Here, archaeological pieces, masks, contemporary artworks, and textiles created by Indigenous communities in Nariño and weavers from Charalá (Santander), emphasize the endurance of living traditions. Rather than presenting heritage as static, the museum foregrounds the constant reinvention of cultural expression—what it calls “a Colombia still weaving its future.”

In total, the exhibition brings together 168 pieces, including nearly 100 that had remained in storage for more than 50 years due to their fragility. Among them are old etchings, rare flags, and objects that once traveled down the Magdalena River to reach the high-altitude capital of Santa Fe de Bogotá. Their exceptional display marks a milestone for the institution and for the country’s historical patrimony.

Visitors encounter not only objects but immersive environments. A multisensory installation projects shifting images onto suspended fabrics, accompanied by a soundscape inspired by Colombian landscapes and local memories. Tactile stations offer replicas with ink and braille textures, making the experience accessible to diverse audiences. Interactive elements invite the public to create postcards, explore regional museum networks, and engage with a digital map linking Bogotá to 45 co-curated displays in 12 departments across the country. Each participating regional museum is exhibiting an object emblematic of its local identity, extending the bicentenary celebration far beyond the capital.

The exhibition reflects the museum’s evolution since its founding as a scientific cabinet of curiosities. Today, grounded in the principles of the 1991 Constitution – cultural diversity, coexistence, protection of natural and cultural heritage – the National Museum positions itself as a space where collective histories intersect with citizen voices. The bicentenary, the museum highlights, recognizes that history is not a fixed record but an instrument for understanding present challenges and imagining future possibilities.

The exhibition at Museo Nacional runs until March 15, 2026, and includes guided tours and workshops. Admission is Free.

Museo Nacional. Cra 7 No.28-66.

Lines on Stone: The Millennial Rock Art of the La Lindosa Range

At the eastern fringes of the Andes, where the Orinoco River Basin unfurls in an ondulating canvas of green, punctuated by majestic rivers and sandstone mesas, lies one of the world’s most astonishing open-air galleries of human existence.

The Serranía de La Lindosa, in the department of Guaviare, is a monumental tableau carved by nature and painted by hands that may have been among the earliest storytellers on the planet. For centuries, these walls stood largely hidden to the world, known only to Indigenous communities and a handful of intrepid explorers. Today, they form the heart of a groundbreaking exhibition in Bogotá’s Museo del Oro: Trazos sobre piedra: Pinturas milenarias en la serranía de La Lindosa, an ambitious, year-long showcase hosted by Banco de la República.

The exhibition that opens on November 28 is the most extensive institutional undertaking yet to unravel the symbols, narratives, and cosmologies that animate a rock-art tradition stretching back tens of millennia. Far from a display of a lost civilization, the Central Bank’s ambition matches that of the cliffs themselves – massive escarpments where hunters, shamans, and master painters returned generation after generation to leave visual testaments of their world.

The story of La Lindosa begins, in many ways, with a single mark. A red smear – thin, elongated, always intentional – painted on the rough face of a stone wall deep in an expanse of canopy and tropical rainforest. To an untrained eye, the pigment blends with natural iron deposits. But to archaeologists who have studied the region for years, it marks the threshold of an extraordinary visual universe. That smear belongs to a constellation of tens of thousands of pictograms across Guaviare and neighboring Amazonian massifs, including the monumental cliffs of the PNN Chiribiquete National Park. Together, they form one of the world’s oldest and largest rock-art traditions.

Archaeologists describe La Lindosa as a cultural landscape, a place where art, geology, ecology, and spirituality intertwine. The Serranía’s towering sandstone walls were formed by tectonic forces millions of years ago, creating natural canvases that humans began to paint long before the earliest agricultural societies emerged.

Only recently have researchers begun to grasp the full temporal depth of these murals. While Europe’s famed Lascaux cave contains roughly 600 images dating to the Upper Paleolithic (between 15,000 and 13,000 BC), the paleo-Indian paintings of Colombia could be far older. In Chiribiquete, analysis of natural dyes, superimposed layers, and stylistic continuity suggests that some images may date back as far as 35,000 BC. La Lindosa shares many of these motifs and techniques, hinting at a cultural horizon that may reach back to the earliest chapters of human imagination.

This immense chronology is not just a scientific revelation – it is a window into a world where every figure, every line, carries meaning. The murals of La Lindosa are filled with scenes of ritual dances, hunting parties, geometric patterns, spirit beings, and animal-human hybrids. They depict jaguars, monkeys, fish, snakes, birds, and the silhouettes of humans with outstretched arms. In some panels, the figures appear in motion; in others, they stand in tight, nearly choreographed formations that suggest communal ceremony. The dazzling variety of imagery points to a worldview rooted in transformation, reciprocity, and ecological intimacy.

One of the most compelling findings to emerge from recent research is the specialized nature of the painting tradition. Archaeologists believe that the most experienced storytellers – shamans, ritual specialists, or highly trained painters – scaled treacherous escarpments to reach spaces associated with spirits and cosmic forces.

These elevated murals often contain the most complex iconography, executed with astonishing precision. Younger or less experienced painters worked closer to the ground, contributing simpler figures or layering their work atop earlier compositions. Over centuries, entire cliffs became palimpsests: surfaces where multiple generations added, corrected, reinterpreted, and echoed the narratives of their ancestors.

The Banco de la República’s exhibition, under Judith Trujillo’s curatorship, mirrors this layered history. Visitors encounter immersive installations, high-resolution photographic panels, pigment analyses, and interactive 3D reconstructions that recreate the sense of standing before the colossal walls themselves. Rather than isolating images, the exhibition places each pictogram within the broader landscape – its geology, myths, and ecological rhythms.

To step inside the exhibition is to enter a world where the boundaries between art and survival dissolve. The rock art of La Lindosa was not decorative; it was a method of world-making. It engaged with spirits, conveyed moral codes, transmitted ecological knowledge, and anchored communities in a landscape that could be both bountiful and unforgiving. Many murals appear near water sources, ancient pathways, or natural shelters – places where human life pulsed most intensely.

Just as telling is the continuity these images embody. Despite colonization, displacement, and the fragmentation of Indigenous territories, the symbolic vocabulary of the Amazon endures. Elements of this cosmology survive in the ritual practices of several Indigenous groups today, whose elders regard the panels not as archaeological remains but as living documents.

As Colombia confronts the pressures of illegal mining, deforestation, and climate change, the need to protect sites like La Lindosa has become urgent. These walls hold traces of human existence long before national borders or written histories were printed. They extend the timeline of pre-Columbian identity back tens of thousands of years, reminding visitors that the Amazon and Orinoco watersheds have always been at the center of innovation, imagination, and spiritual awakening.

Inside the Gold Museum’s hallowed halls, visitors will pause before the vivid reds – their unexpected brightness, their persistence through rain, wind, time. These pigments, ground from seeds, minerals, and endemic plants, were not chosen at random; they were sacred. They signaled life, danger, transformation. They were meant to endure.

Whether the ancient painters imagined their work surviving 30,000 years is just one of many unsolved mysteries. Their names may be lost, but their visions endure – a vast, breathing archive that continues to astonish and challenge us.

Guests to this landmark exhibition are not mere spectators either, but participants in La Lindosa’s vast “Sistine Chapel” – an offering handed-down to generations, and carried forward through the endless corridors of time.

Visitor Information – Museo del Oro

Museo del Oro, Banco de la República

Cra. 6 No. 15-88.

Exhibition runs until November 27, 2026.

Opening Hours

- Tuesday–Saturday: 9:00 a.m. – 7:00 p.m.

- Sunday: 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

- Monday: Closed

Admission: COP $5,000

Follow the exhibition on social media: Instagram @MuseoDelOro #LaLindosa #MuseoDelOro