Petro–Trump Phone Call Defuses U.S.–Colombia Tensions

It was a frustrating night for the roughly 6,000 supporters gathered in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolívar to hear President Gustavo Petro deliver what many expected to be a fiery, anti-imperialist address.

After waiting for hours in cold, rainy conditions, demonstrators waved placards reading “Yankee Go Home,” “Out Trump,” and “Respect Colombia,” anticipating a confrontational speech aimed squarely at U.S. President Donald Trump following weeks of diplomatic tension.

Instead, when Petro finally took the stage, the tone of the rally shifted abruptly.

The Colombian president opened by announcing that he would not deliver his prepared speech. Rather than launching into the expected denunciation of Washington, Petro told the crowd that his delay was due to a lengthy phone call with Trump — a revelation that visibly stunned the audience.

As Petro spoke about the conversation, the plaza fell largely silent. Each mention of Trump appeared to drain the rally of its energy, replacing chants and applause with uneasy quiet. What had been billed as a mass show of resistance against U.S. pressure became an unexpected account of diplomatic rapprochement.

According to Petro, the call — conducted with simultaneous translation — lasted close to an hour and marked the first direct conversation between the two leaders since Trump’s return to office. “Today I came with one speech, and I have to give another,” Petro told supporters. “The first one was quite hard.”

A source at the presidential palace told El Colombiano that Petro appeared relaxed during the exchange, smiling several times as he spoke with Trump. A photograph of the moment, later shared by Petro, showed him seated at his desk mid-conversation.

Petro said the discussion focused primarily on drug trafficking, Venezuela and other bilateral disagreements. He acknowledged that significant differences remain but argued that dialogue was preferable to confrontation.

“I know that if anyone were to harm me — in any way — what would happen, given Colombia’s history and the level of support we have reached, is that the Colombian people would enter into conflict,” Petro said during the rally. “If they touch Petro, they touch Colombia.”

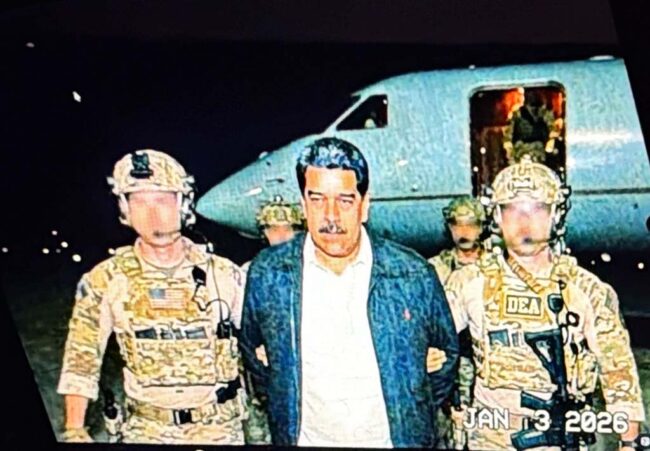

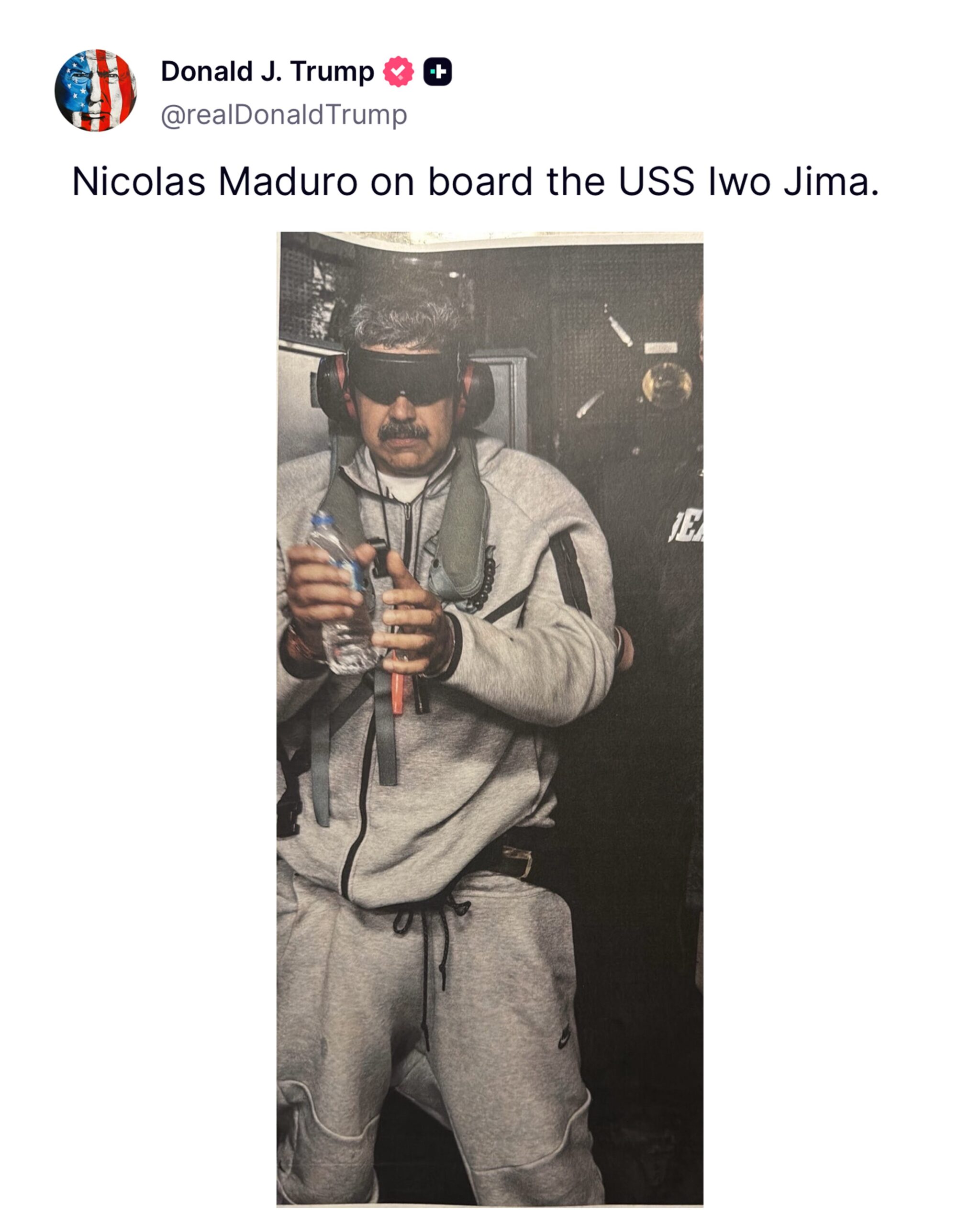

The remarks were a response to Trump’s recent comments suggesting that a military operation against Colombia, similar to the one carried out in Venezuela, “sounds good.” Petro, however, struck a notably more conciliatory tone on Wednesday, saying Trump “is not foolish,” even if he disagreed with him.

In a further surprise to supporters, Petro stated publicly that Nicolás Maduro was not his ally, claiming the Venezuelan leader had previously distanced him from Hugo Chávez by preventing him from attending Chávez’s funeral.

Shortly after the call, Trump issued a statement on his Truth Social platform confirming the conversation and signalling a thaw in relations.

“It was a Great Honor to speak with the President of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, who called to explain the situation of drugs and other disagreements that we have had,” Trump wrote. “I appreciated his call and tone, and look forward to meeting him in the near future.”

Trump added that Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Colombia’s foreign minister were already making arrangements for a meeting at the White House in Washington.

Petro confirmed that further discussions would be needed, particularly regarding drug trafficking figures, the role of the ELN guerrilla group along Colombia’s borders and Venezuela’s political future. “We cannot lower our guard,” Petro said. “There are still things to discuss at the White House.”

The president also revealed that he had spoken days earlier with Venezuela’s interim leader Delcy Rodríguez and had invited her to Colombia — a disclosure likely to further complicate regional diplomacy.

What was intended as a show of defiance against Washington ultimately became a public demonstration of Petro’s willingness to recalibrate his strategy, leaving his hardline supporters confused and critics questioning whether the president had overplayed the politics of mobilisation — only to pivot, unexpectedly, toward negotiation.